The Birthday Greeters of Barbur Boulevard

Phil and Quinn called it the “Object That Has No Name” because that was easier to say than “small non-theater sort of free standing marquee that you can use to make changeable signs with and probably put on the sidewalk” since no one knew what the correct term for it would be.

It must once have had a generic name under which it was manufactured and sold and appeared in a salesman’s catalog, and was maybe even patented (and who knows but what there might even have been competing products with names like The Acme Silent Sidewalk Salesman or The Miracle Midget Marquee), but none of them ever found out what that name was.

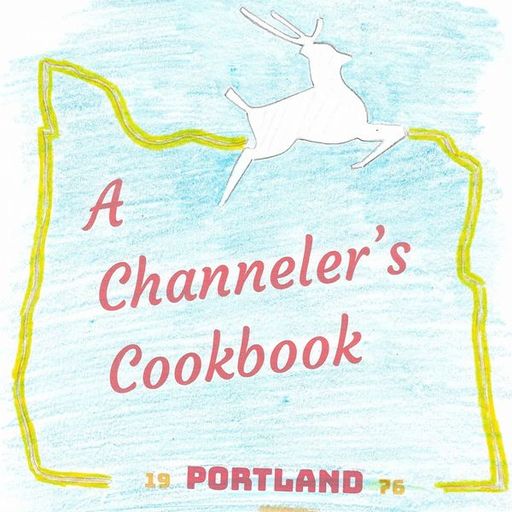

The Object’s ultimate connection with A Channeler’s Cook Book is maybe a few bubbles off plumb in places, though otherwise straightforward. But it has been determined in the course of the book’s initial smoke-charged Inception and during each of the many subsequent spontaneous smoke-charged renditions of the Inception, that the length of the product of the Inception, a testament not only to the wordy discursiveness for which the smoke is well known, but to an acute appreciation that transcended mere discursiveness of the way in which certain events – a physical book for instance – can have well-defined beginnings and endings, while other events – the intellectual pedigree of a book for instance – are merely the current tail end of a confluence of serendipity and a potentially infinite regress of nonlinear cause and effect, nonlinear to such an extent in fact that even recent events, events occurring well after the Inception and all that led up to the Inception, nonetheless wind up being seamlessly spliced into the existing narrative of the Inception, making the ends of causal threads harder to find but freeing the teller from the tyranny of chronology.

Or at least this is the way Quinn tended to put it when the bong had made a few rounds and the smoke had done its job.

Quinn nearly tripped over the Object That Has No Name on the day he decided that the tipi he shared with Sheila needed its own well because the tipi was situated just far enough away from the Red House to make using its faucets to fill five gallon cans with water for drinking and cooking an annoyance. Oregon is not without water but hardly any of it can be found on the Skyline ridge that overlooks Portland. It all seeps down to somewhere else so that the wells on Skyline go deep. The Red House had its own well, sunk sometime before the war but neither George nor anyone else in the Red House new how deep it was.

Because new construction on that part of Skyline was rare and the existing houses old, neighborhood well expertise had either aged out or moved away. Having sunk a single well would confer specialist’s status and having sunk three would make you a consultant. Such a consultant lived a mile and a half up the road and this is where Quinn went. The consultant was Evelyn Smyth, The Madonna of the Mountain, the Virgin of the Crossroads, where she worked the cash register at the Plainview Grocery and according to Quinn, at forty-six years old and still physically perfect, the finest example of womanhood that no one would ever be allowed to enjoy.

Where the dirt track leading up to the Madonna’s trailer met Skyline was a mail box and a wrought iron post and bracket with a cedar shake hanging from it by a pair of brass chains and the words Free Advice beautifully carved out and painted white. An hour later, The Madonna and Quin were chatting out in the fair weather gazebo. The Madonna was stretched out naked on a chaise lounge and had just finished a lengthy disquisition on the ins and outs of drilling wells, during which she’d also finished off Quinn’s hopes by eventually answering, in her down market London accent, the question he’d come with: “Oh, up where you are, you’re going to have to think in terms of drilling 600 feet or so, I shouldn’t wonder.”

With four or five large mugs of spearmint tea on board Quinn excused himself and walked across the open field behind the Airstream toward the stand of Douglas firs at the far side of the property. His mind concentrated on finding a way around 600 feet of drilling, he went past where he would normally have entered the stand and ended up tripping over a mound of sedges and vines.

And uncovering the Object That Has No Name.

A bucket of water and a lot of sponging later, it was revealed to be a species of ground-dwelling marquee. Two plastic rectangles four feet tall and three wide held together at the top by hinges and at the bottom by lengths of chains. Ranks of slots running horizontally across front and back sides would hold the lettering. Quinn saw that it could be stood up on the side walk in front of a business and used to announce store hours, this week’s blowout sale or a diner’s blue plate special. The Madonna saw that it could clutter up someone else’s property instead of hers and that Quinn was just the guy to do the cluttering.

Quinn was astonished to discover that The Madonna wasn’t delighted to possess a thing – whatever you called it – with such potential but was grateful when she insisted that since he’d found it and since it would otherwise have lain beneath the accumulating vegetation forever, it was only fair that he be allowed to take it home with him. After a final cup of tea – a heartrendingly smoky Oolong this time – and a shared magic brownie, Quinn carried the Object out to the car, debating with himself whether his good luck was due to the Madonna’s generosity or to an uncharacteristic bout of shortsightedness on her part.

A few months later when Quinn hadn’t yet discovered any of the many potential uses that it must have, he decided that what a thing to be used for making signs needed was people to read the signs after they’d been made, and that this required a place with people nearby. So the next time he drove down the hill into Portland to lead a walking tour, he stopped by the Eddie Haskell Bunker and stood the marquee up outside the side door. Whatever letters that might have been sold with it had not survived the years of silent exile in The Madonna’s field, but some 3X5 note cards and a black felt tipped pen did the job. When he drove off, the marquee said MAKE ME SAY SOMETHING.

When Phil and Yuri got home that evening, Yuri said “No thanks” as she walked past, while Phil just ignored it. When Bekka got home she shouted “Cool-OH!” She removed the words MAKE ME SAY, leaving only SOMETHING, said “Say goodnight, Gracie” to the marquee and went in the door. That night after dinner she drove to Fred Meyer’s, bought packages of note cards, cleared off the work table in her room, brought out pens, paint and brushes and created the first set of 26 letters plus punctuation.

A few days later she stood it alongside the brick path leading to the unused front door. It said WELCOME TO THE EDDIE HASKELL BUNKER. When that novelty had worn thin, Yuri brought it inside where it was used to record phone messages. There were hardly ever any of those, so it was set up near the entrance to the kitchen and used to advertise weekly specials of fictitious items.

The next Sunday afternoon, the bunker’s monthly driveby free food extravaganza was enhanced by the presence of a sign on the sidewalk that read FREE FOOD FOR NO PARTICULAR REASON.

There was a twisted Chinese fortune cookie phase. Once Phil came home with many bong hits to his credit, spent a good 15 minutes standing outside the side door, admiring how the lock and key matched up so effortlessly and so transcendentally beyond mere functional teleology, and worked together in a way that was close to dance, and eventually walked inside, only to see the Object saying to him, EVERYONE BELIEVES YOU’RE PARANOID.

Irony not being the strong suit of stoned persons, there followed a long and unhappy night during which Phil felt he really ought to reassure Yuri that he wasn’t in the least paranoid while Yuri kept telling him that she knew that. And yet, thought Phil, there was that message made by someone in the house. And worst of all is the fact that if one hears oneself saying over and over that one is not paranoid, one begins to hear the protestations as a manifestation of that which is being denied, and there’s no recovery from that counterclockwise spin down the brain’s drain.

Eventually Yuri sensibly gave up on both sleep and argument and they went down to the living room and watched Day of the Triffids on TV to get Phil’s mind off the subject of paranoia, because, reasoned Yuri, a little bit of vegetable cathexis might be just what her husband needed. It was working out nicely until Tom Peterson came on and appeared to knock on their television screen, look directly at them and call out “Wake up!”

“So he really was able to tell that I was falling asleep, and that’s not just me being paranoid,” said Phil. “Is that what you’re telling me?”

“No, honey. Tom Peterson doesn’t know who you are. You remember that television isn’t two way, right, honey?”

“I do remember, of course. So I am being paranoid.”

“No, you’re just being stoned. Big difference.”

“Ha! Now I’ve defeated you with your own logic. Everybody knows that stoned people often get paranoid. Didn’t see that one coming, did you?” Phil clapped his hands together in triumph and gave Yuri a kiss on the cheek.

In the morning Yuri took the Object That Has No Name, folded it up, removed the lettering and said to Phil, “Get this thing out of here. Think of something positive to put on it and go out and let people see it. Make it good. Use your imagination. Don’t hide your light under a bushel, and so forth.” She went back to drying dishes and singing “I just want to celebrate,” now into its second week as her constant companion.

Two mornings later Phil and Bekka blew up a dozen party balloons and tied them together with string since ribbon was a little out of budget. Then Phil placed the Object folded flat on top of his head, which was the only way to carry it, and the two of them hiked up onto Barbur Boulevard where the morning commute was in full flood. They found a place on the sidewalk that wasn’t in front of a business and wouldn’t impede anyone walking on the sidewalk. In fact, it was one of those peculiar missing sidewalk squares – a square space full of grass instead of concrete. Unclaimed land upon which Phil set the Object while Bekka tied on the balloons. Then Phil added the lettering. HAPPY BIRTHDAY CINDY AND ROSHANNA. Cars honked.

“Everybody loves a birthday.”

“Everybody loves being happy for someone else,” said Bekka, who that night drew up decoration lettering: birthday candles, gift wrapped boxes with bows, cupcakes. The next morning was Harry’s birthday and the next that of the Hazelton Triplets. Bekka said, “You know, once in a while we’re might accidentally be getting it right.”

More than once they found a note scotch taped to the Object or folded at the base beneath a small stone to keep it from blowing away, with the name and birth date of a child. For Phil this was playing loose with the essential randomness of the whole effort, but the parents of little Michelle and the others were accommodated.

Keeping to the theme of positivity they sometimes paused from birthdays and branched out into a more general unspecified celebration. CONGRATULATIONS MRS. DIGRASSI. WE KNEW YOU COULD! They developed a fan base. It being light and quick work, one of them was able to attend to the Object and its messages of positivity almost every morning. Doing it consistently at the same time meant that commuters driving in at the same time were likely to see them often.

Six months into the project each morning’s two-minute changing of the message was carried out to the frequent honking of horns. They experienced fleeting fame among the items in the Willamette Week’s city column. “Best Name in Portland: Xerpha Borunda. Best Spontaneous Charity: The Birthday Messengers of Barbur Blvd.”

There were setbacks. Sometimes they arrived to find the Object knocked over. Twice there was a note left on the Object by someone who said they found it knocked over and had set it up again. Sometimes the lettering was stolen. Sometimes the lettering was rearranged in very un-birthdaylike ways. Once a car pulled over while they were arranging the day’s message and a woman got out and chewed them out for getting her daughter’s birthday wrong by a full week. Did they have any idea how that made her daughter feel? When a slightly disoriented Bekka and Phil admitted to having no idea, the woman drove away angrier than when she’d arrived.

On the whole the setbacks were by far outweighed by the waves of positivity that Yuri had insisted on. But on the same whole, there were an increasing number of mornings when they made the trip mainly because they felt it was expected of them. And if they arrived at the Object some mornings a little grumpy, the honking of the passing cars was usually enough to provide another day’s worth of enthusiasm. Still, more and more it was like sending a birthday present to a relative that you aren’t all that close to because of how hurt you’re afraid they might be if you didn’t send them one. Eventually the morning arrived when Phil realized that he would never again feel the same charitable pizzazz as when they’d first started.

“Then don’t let a good thing die a lingering death,” was Yuri’s advice. That night Bekka created a beautiful red heart that looked three dimensional, big enough to cover the top three rows of lettering. The next morning, the Object was adorned with the heart and said, IT’S BEEN WONDERFUL. U R WONDERFUL. They left it a few days and then packed it back to the bunker.

The following Sunday the ice cube tray pipe made the rounds and the Object sat propped against the wall in the corner of the living room, saying WHAT NOW? The red housers had driven down the hill for the monthly drive-by feast at the bunker but had arrived late so that there was barely time to move the picnic table down next to the sidewalk and load it up with food before the guests, random pedestrians and drivers began stopping by, and no time at all to light up. It was Arlene who noted how unusual it felt to stuff yourself with food first and then to get the munchies. “It’s like I’ve got munchie credits sitting in my stomach. No fridge raids required. It’s kind of fun.”

“It’s the spontaneous breaking of your own conventional patterns that you find delightful,” explained Quinn.

Which was Yuri and Bekka’s cue to excuse themselves because Quinn was about to go full Zen. George was on shift and so was not there to drawl out some fake ghetto homily at Quinn when it was time for him to climb down off it. Phil was usually argumentative in response but that just made it more intense. Sheila was, as always, seated slightly apart, sketching the scene in her visual diary and ignoring Quinn as only an experienced Significant Other can. And Danny And Arlene were having a full bowl of it and chewing happily.

Phil, still feeling at sea after the retirement of the fictional birthday project, suggested that maybe one way they could all be a little more Mahayana would be to start accepting donations at the monthly drive-by free food extravaganza. Danny thought it was a good Bodhisattva idea. Bekka reminded them that all the fun of giving away free food is made problematic when the food turns out to be not free.

“The real bodhisattva way,” Quinn said, “would be to have the picnic table with place settings and a big center piece, and you would pay to get a seat at the table. And then the money would be used to buy food for people somewhere else.”

Arline laughed. “So the deal is, you get all hungry but someone else gets to eat. Boss!”

“That’s a purer form of the bodhisattva ideal,” Quinn intoned as he inhaled.

Bekka crossed the living room, sat beside the Object and began digging into the box of lettering. Two minutes later, the Object said IF YOU MEET A ZEN PHILOSOPHER ON THE ROAD, KILL HIM.