YGTMTGTF

There’s a lot to recommend a career in the retail illegal drug trade. The work is both steady and recession-proof. While the rest of the economy cycles through boom and bust, retail drug sales go from pretty good to really good and back again. The product sells itself. But advertising isn’t the only overhead you don’t have to factor into the cost of doing business. There are also no license or certification fees, no dues for professional associations, no taxes.

And the work is family friendly. Hours are flexible so getting the kids to dental appointments and soccer practice and attending PTA meetings isn’t at the whim of your boss. There is a positive psychological component that often goes unremarked. You not only are freed from having to work in an office or an assembly line, but you are spared the more demeaning forms of retail sales like selling Fuller brushes door to door, or Avon products. No doors are slammed in your face because there’s no one to talk into anything. There are no potential customers, just customers, and they gladly come to you. Better still, the psychological benefits of positive social interactions have been demonstrated by many studies and the retail illegal drug trade can be thought of as an ongoing sustainable positive social interaction.

While it’s true that these transactions do not result in friendships in the usual sense, people are nonetheless generally happy, or at least relieved, to see you and while that happiness may be utilitarian in nature, nothing prevents the transactions from being genuinely friendly and only the limits of one’s own generosity keep one from selling the pharmaceutical equivalent of a baker’s dozen to new and established customers alike.

Another compelling (many would say the most compelling) reason why the retail illegal drug trade recommends itself, especially when compared to the legal trade, is the high level of government support at both the state and federal levels. The government is very pro illegal drugs. For the many retailers who think of themselves with pride as independent small business persons and who want no part of government interference, it is a bitter – though a perfectly legal – pill to swallow to acknowledge the reality that without direct government interference, normal market forces allowed to play out on their own would drive nearly all smaller mom and pop drug retailers out of the trade and drastically lower the price of the product.

To get a sense of just how important government support in the retail drug trade is, consider two drugs that are universally popular with human brains. One is somewhat stronger than the other. Both cause the body to become flooded with tertiary amines, and it is this that accounts for their popularity. (In evolutionary biology it is sometimes said that a chicken is an egg’s way of making another egg. In a similar way it can be said that a body is a brain’s way of going out and getting more tertiary amines.)

The less strong of the two drugs earns its producers and retailers billions of dollars a year but suffers the disadvantage of being legal. Its retailers are forced to pay a huge overhead – for expensive vending outlets and equipment in each neighborhood, for the costs of constant new product development in order to stay ahead of the competition, for marketing and advertising, taxes and all the other normal expenses of a business. Perhaps one in a hundred retailers can manage to make a go of it under such conditions and the great majority of those barely manage to stay profitable. All the rest must accept minimum wage positions with one of the monopolist vendors in the trade or find work in some other profession.

The stronger of the two drugs enjoys government support to the tune of forty or fifty billion dollars a year spent in maintaining and enforcing the illegal status of the trade, and with that support earns trillions of dollars for its producers and retailers all along the supply chain. While it is true that the producers spend a few tens of billions of dollars each year thanking selected government employees for their leadership, it’s barely enough as a percentage of profit to even qualify as a true business expense.

Of course the producers and larger distributors make most of the money, but there’s still plenty left over to ensure that those small retailers willing to work hard and play by some of the rules can provide well for their families and can live out the traditional intergenerational dream of making sure that their children are left better off that they were.

So with all the advantages to entry into the retail illegal drug trade, Phil was surprised at how hard getting started was turning out to be. Now, his drug of retail choice was not one of the two in the example above but rather an anticholinergic with some atropinic and other brain-friendly features. While the brain is delighted to encounter this drug, in this particular case the brain partners with the body on a more equal footing than it does with those just mentioned, for along with the euphoria, a number of somatic activities are often experienced, from massage and sex through eating the contents of a refrigerator. So the difficulty for Phil lay not in the choice of product. Nor in access to the product. Unlike the amine-inducing agents which require extensive processing and logistics, Phil’s drug is extracted from a particular one of the many species of the hemp family that grow readily in Oregon and which requires no postharvest processing at all. Neither was access to the producers a problem. Phil knew people who knew people and he himself had a good reputation, or rather since he had no previous history in the trade, did not have a bad one, which in some circles is just as good.

No, for Phil the difficulty boiled down to startup capital and it was the one thing that he had just assumed would work itself out. That assumption, presented to Yuri and Bekka afterwards, amounted to the idea that someone would simply front him the product on credit with his good reputation as collateral and that he would quickly pay them back with interest and that everybody would be happy and it would turn into a regular thing profitable to all.

His first thought had been a private loan. But no one he trusted to ask had that kind of spare change and those who did were best shielded from the news that he was going to set himself up in the retail illegal drug business. So trusting that a good business proposition would prevail over natural caution he went to southern Oregon for a series of audiences. One or two went well only in the sense that his interlocutors found him charmingly wacky. One or two went less well when it was suggested to Phil that asking for product without a means to pay for it was a form of bridge burning and that it might transpire that the next bridge he burned could have him tied to it. After three frustrating days he called it quits and drove back to the Portland. For a few days after he went to work and came home and went about his routine, but his head was still arguing with the recalcitrant growers outside of Ashland.

Then one morning the Madonna herself came down off the hill with a plain white envelope with nothing written on it, which she slid through the mail slot in the front door. Then she taped a note to the side door. “Check your mail. Good luck, Evelyn.”

“Listen to this!” Phil said to Yuri that night as she stood at the bathroom mirror in her night gown and brushed her hair. Bekka was standing in the hall outside the bathroom door, leaning against the wall and juggling golf balls. “Came in a blank envelope. The Madonna got it from somebody who probably got it from somebody. Are you ready for this? ’I talked to someone you just talked to. Are you real? If you’re real, come back down. If you aren’t, safest thing for you is to stay away.’ That’s it. No name, and typed, not hand written.”

Bekka whistled. “Drugs! Adventure! Mystery!”

Yuri said, “How long have we been together? and I never thought to ask you if you were real.”

“I have to drive back down.”

“OK, but go prepared. Get the printing done and make up a sample package to take with you. I don’t know about real, but that’ll make you seem more serious.”

Late the next day, Phil climbed into the truck with his salesman’s sample: a plastic baggie containing catnip for verisimilitude and folded and placed inside along with the faux product as a label, a small four-color illustrated flier.

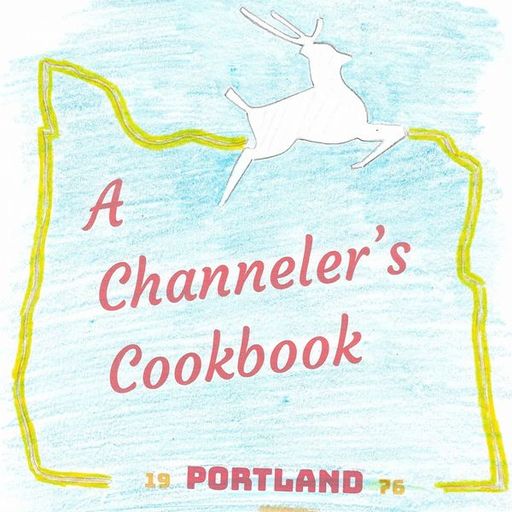

At the top of the flier Bekka had drawn Cookie Monster, hands full of cookie and mouth dribbling crumbs. He had bloodshot eyes and wore a matching red beret with a black “420” stitched on the front. The middle of the flier was crowded with trippy font taken from a Stanley Mouse poster for some long ago Grateful Dead concert, mandarin orange lettering against a jade background. It said

You Get The Munchies, They Get The Food

This is a 30 gram ounce of genuine Oregon-grown

marijuahoocie. It was kindly donated free of charge

to the YGTMTGTF project. 100% of the proceeds

from the sale of this fine product are given

(anonymously) to a non-governmental charity that

feeds poor children both here and in developing

countries.

ACCEPT NO SUBSTITUTES. PLEASE BE DISCREET

In the center of the blank white reverse side was the canonical black Zen calligraphed circle, because Quinn really really really wanted her to put it there.

Before Phil started up the Truck, Yuri leaned in the open window and asked Phil if he planned on employing the term “bodhisattva” in his pitch to the mystery grower. “I think maybe I’ll just talk about helping out when the opportunity arises.”

She laughed and kissed him. “See? I knew you were real.”